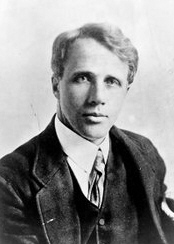

Clement Clarke Moore

As I was searching and compiling all the information about Clement Clarke Moore, I ran across this very complete and articulate article and decided to throw away my scribbled notes and post this article written by Jeff Westover.

Clement Clarke Moore: Father, Patriot and Poet

By Jeff Westover

Clement Clarke Moore was one of New York's wealthiest men. And clearly, one of it's most highly educated.

He was born in 1779 to Benjamin Moore, a patriot and an Episcopalian minister. His mother was Charity Clarke, a feisty and ardent supporter of the American cause. He inherited from her side of the family a good portion of land that would someday become the Chelsea District in New York City.

For young Clement C. Moore, his life's work did not lay in the ministry as it did his father. He had a well developed love of language and pursued the learning of ancient dialects of Hebrew, Greek and German. But he was a man of profound attachment to family, home and church. He donated property and for a time assumed the entire debt of Saint Peter's Church.

He married a woman named Catherine Elizabeth and was shamelessly devoted to her. While courting her, Moore wrote to his future mother-in-law that he would carve her name into trees. Together, they had nine children. When her life unexpectedly was taken while she was yet 30 years old, he was devastated. But he assumed her duties and enjoyed fond relationships with his children and grandchildren.

It is not hard to imagine then what transpired that snowy Christmas Eve in 1822. Catherine sent her husband out into the elements to get one more turkey, which she and the children were preparing as a donation to the poor. Their home, with six children at the time, was one filled with love and warmth and tradition.

Clement ventured into town, his coachman being a jolly, round fellow with a long white beard and a most cheerful disposition. After he purchased the needed turkey from Jefferson's Market, with sleigh bells merrily ringing in his ears as the snow fell that Christmas Eve day, he composed a short poem.

Moore returned home with the turkey and the family traditions of Christmas took hold. He added to them by delighting his young children that night by the fire with the first reading of "The Night Before Christmas", the poem he had composed that very afternoon. Then, he tucked his handwritten copy of his creation away and gave it no further thought.

But his poem had made a powerful impression upon his children, who some months later shared it with a visiting family friend. This same friend, not knowing that Moore's sole intent was to keep the poem private, sent it to the Troy Sentinel, where it was published anonymously just before Christmas in 1823.

The poem quickly became beloved of the public and spread Moore's name around the globe. It shaped the imagination of who Santa Claus is and what he looks like. Moore's work provided inspiration for Thomas Nast, an illustrator of political cartoons who gained notoriety as well for his early wood engravings of Christmas scenes published in Harper's Weekly.

By 1844, Moore included A Visit from Saint Nicholas in a published collection of his poetic writings. He was a giant in his community, a trustee of Columbia University, well known in academia for his scholarship in ancient languages and his real estate dealings shaped modern-day Manhatten. But the world knows him and holds him dear for the "trifle", as he called it, that he penned for his children on a chilly sleigh ride back home from the market on Christmas Eve of 1822.

© 1991-2006 - All Rights Reserved